Evidence-based Wellbeing Coaching: Insights from My Doctoral Research Journey

Jan 27, 2026PhD research rarely unfolds in a neat, linear way. It’s iterative, reflective, and often shaped as much by uncertainty as by clarity.

My doctorate emerged from a practical question that kept coming up in both my organizational work and my coaching:

How can we offer proactive, evidence-based wellbeing coaching in a way that feels accessible and genuinely useful?

As I explored this, one idea kept resurfacing: mindfulness. It’s frequently positioned as a core part of wellbeing support, particularly in preventative and resilience-focused approaches.

But in practice, I noticed a gap.

Much of the conversation around mindfulness in coaching still assumes a meditation-based approach. Many people benefit from meditation. Others don’t. Some find it difficult, disengage from it, or simply don’t see it as a good fit for their lives or work. That matters when we’re designing coaching interventions intended for broad, real-world use.

What interested me wasn’t rejecting mindfulness, but widening how it’s understood.

This led me to socio-cognitive mindfulness, developed by social psychologist Professor Ellen Langer. Rather than meditation, it focuses on everyday cognitive processes like noticing new information, reframing context, and holding multiple perspectives; processes that already sit at the heart of effective coaching.

In coaching terms, it’s less about calming the mind and more about flexing the mind.

My doctoral research followed a structured intervention-development pathway. That meant moving systematically from reviewing the existing evidence, to stakeholder insight, to program theory, to intervention design, and then to testing the idea.

This blog shares that journey through five publications, each marking a key stage in what I learned about coaching psychology, wellbeing, and socio-cognitive mindfulness.

The core aim of the doctorate

The overall aim of the research was to develop a coaching intervention grounded in socio-cognitive mindfulness theory to support wellbeing development in non-clinical adults. This focus reflected a commitment to proactive wellbeing support, helping individuals strengthen awareness and resilience earlier, rather than waiting until difficulties require clinical or therapeutic intervention.

Across the project, one insight kept reappearing.

When participants described meaningful changes in their wellbeing, they rarely talked about fixing problems. Instead, they described increased cognitive flexibility.

Not “I fixed the problem.”

But “I can see more options.”

“I’m less rigid with myself.”

“I respond differently now.”

That insight has stayed with me. It continues to shape how I design training, supervise coaches, and think about evidence-informed work through AoCP.

Starting with the evidence

The doctorate began with a systematic review published in the International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring¹. Before designing any coaching program, I needed to understand what the existing evidence actually showed about socio-cognitive mindfulness interventions.

The review explored how socio-cognitive mindfulness is activated in non-clinical adults, what outcomes have been reported, and which insights seem most relevant for coaching contexts.

One of the clearest findings was that socio-cognitive mindfulness can be activated through practical, active exercises, not just extended programs. These interventions were associated with a range of wellbeing-related outcomes, including changes linked to intrapersonal awareness, interpersonal functioning, and how people relate to context.

For coaching psychology, this mattered. The mechanisms behind socio-cognitive mindfulness, learning through experience, perspective-taking, and flexible thinking, are already central to effective coaching practice.

This paper provided the foundation for everything that followed.

Checking the idea with real coaches

The next step was to explore whether a wellbeing coaching intervention based on socio-cognitive mindfulness would actually be acceptable in practice. This work was published in the International Coaching Psychology Review².

Rather than assuming acceptability, I invited practicing coaches to engage with the proposed intervention design and share their views on what would support or undermine its effectiveness.

Three themes stood out.

First, clear contracting really mattered. Coaches emphasized that wellbeing-focused work needs explicit boundaries, expectations, and clarity around responsibility. Contracting wasn’t a formality. It was part of the intervention itself.

Second, group dynamics and psychological safety were front and center. Group-based learning offered rich opportunities for shared reflection, but it also introduced risks. Coaches highlighted the importance of pacing, containment, and designing for safety, especially when people are exploring wellbeing.

Third, autonomy and engagement were seen as essential for sustainability. Coaches stressed that wellbeing development depends on participants feeling ownership of the process, rather than relying on the coach, the group, or the model to carry the change.

This stage significantly shaped the intervention design. It reinforced that acceptability isn’t something you assess at the end. It has to be built in from the start.

Turning theory into coaching practice

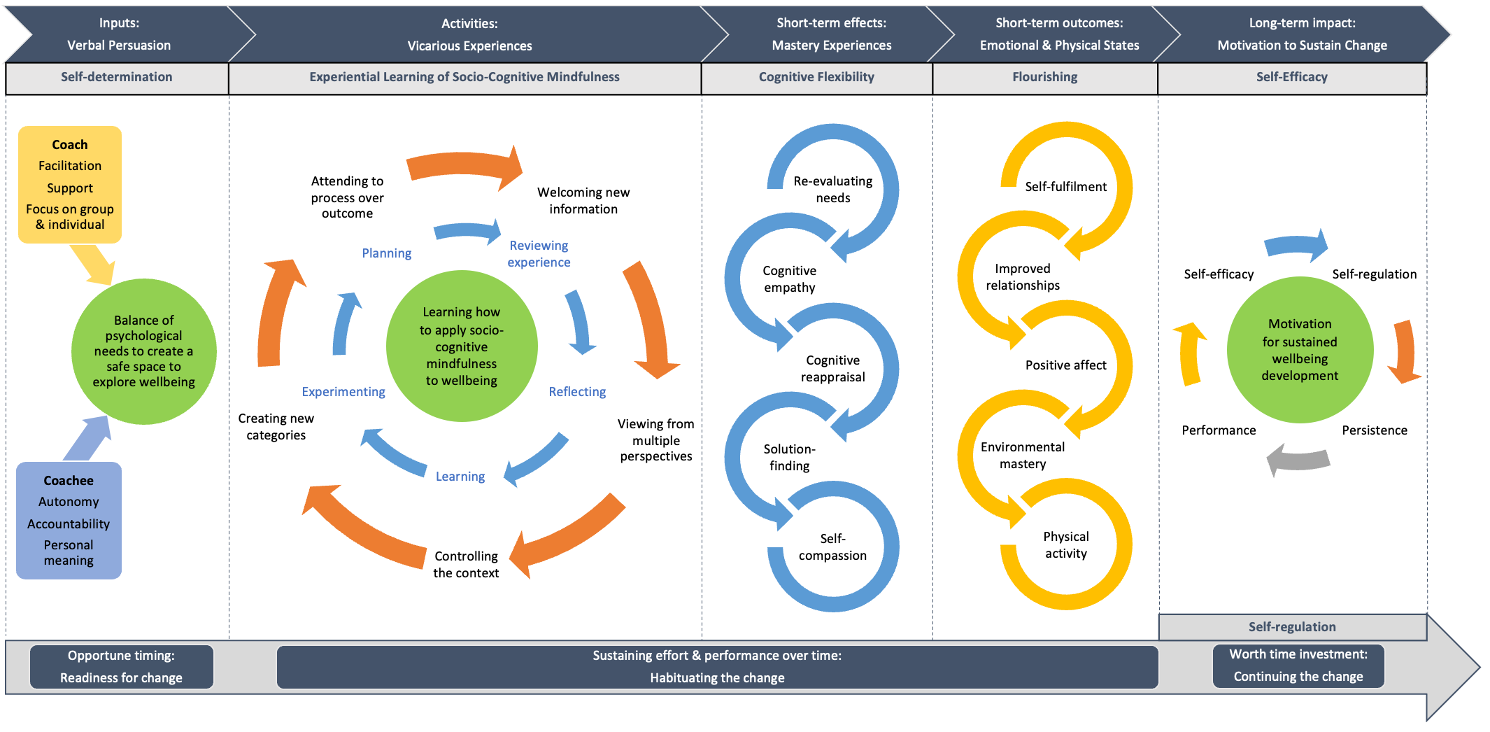

With evidence and stakeholder insight in place, the research moved into intervention development. This work was published in The Coaching Psychologist³.

At this stage, I developed a clear program theory and logic model, and then translated that into a prototype coaching intervention suitable for feasibility testing. This part of the journey involved many design decisions that often stay invisible in coaching research.

The intervention was structured around five socio-cognitive mindfulness processes:

- prioritizing process before outcome

- welcoming new information

- accepting more than one perspective

- reframing context

- expanding categories by creating new distinctions

These processes were embedded into coaching through psychoeducation, coaching questions, experiential activities, and between-session practices.

One of the key learnings here was that intervention development is rarely linear. Evidence, ethical considerations, practitioner judgment, and practical constraints all interact. Being transparent about that process is especially important in coaching psychology, where real-world application often requires flexibility.

What happened when the program was tested

The next stage was to assess feasibility, reported in the International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring⁴.

This study explored recruitment, attendance, adherence, acceptability, and early outcome signals when the intervention was delivered to participants.

The feasibility indicators were encouraging. Participants attended, engaged, and completed the program, and feedback suggested that the intervention was acceptable and well received.

The outcome findings were more nuanced. While there were indications of positive change for some participants, the intervention didn’t appear to be effective for everyone.

This was an important moment in the research. In wellbeing work, it’s easy to overstate impact. A more responsible evidence-based stance is to acknowledge variability and treat it as useful information rather than a failure.

Making sense of the change process

The final publication, again in The Coaching Psychologist⁵, focused on participants’ experiences of the program and how they made sense of change.

Four themes captured their journey:

- balancing coaching tensions to support self-development

- adopting a learning mindset to develop socio-cognitive mindfulness

- improving wellbeing through cognitive flexibility

- moving through stages of motivation for change

What stood out most clearly was how participants described wellbeing change. It wasn’t primarily about symptom reduction or simply “feeling better.” Instead, it was about becoming less rigid, more open-minded, and more able to respond thoughtfully to challenges.

This reinforced what had been emerging throughout the doctorate: cognitive flexibility appears to be a key mechanism through which wellbeing develops in this context.

What this research means for coaching practice

This doctoral journey reshaped how I think about wellbeing coaching and mindfulness-informed practice.

A few implications continue to guide my work through AoCP:

Mindfulness in coaching doesn’t have to mean meditation.

Non-meditative, socio-cognitive approaches can offer a more accessible route for some clients and practitioners.

Design really matters.

Contracting, autonomy, psychological safety, and pacing aren’t optional in wellbeing interventions, especially in group settings.

Variability is part of the picture.

An intervention can be feasible and acceptable while producing different outcomes for different people. That insight supports reflective, ethical coaching practice.

Mechanisms matter as much as outcomes.

Across the research, wellbeing change consistently linked back to flexibility in thinking, experiential learning, self-regulation, and self-efficacy.

From research to application

One of my core motivations for this doctoral research was to ensure it had practical value, not just academic relevance.

The insights from this journey now underpin how I design coach training, supervise practitioners, and think about psychologically informed wellbeing work through AoCP. They’ve also shaped a practical self-coaching resource designed to make these ideas more accessible beyond academic and training contexts.

The Advanced AWARE Self-Coaching Guide translates socio-cognitive mindfulness into everyday self-care and reflective practice. Rather than focusing on techniques or prescriptions, it supports flexible thinking, perspective-shifting, and more intentional responses to the demands of work and life.

In a companion blog, I explore the guide in more detail, including how socio-cognitive mindfulness can support sustainable self-care for coaches and practitioners, and how this approach differs from more traditional, technique-led mindfulness practices.

If you’d prefer to go straight to the resource, you can access the free Advanced AWARE Self-Coaching Guide directly:

Thanks for taking the time to read this reflection on my research. I hope it offers something useful for your own thinking about wellbeing, mindfulness, and coaching practice.

If you’d like to read any of the articles referenced in this post but can’t access them through the journal websites, feel free to email me at [email protected] and I’ll be happy to help.

Katie

References

-

Crabtree, K., & Swainston, K. (2024). A systematic review of socio-cognitive mindfulness interventions and its implications for wellbeing coaching. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, 22(1), 84–108. https://doi.org/10.24384/jek2-d087

- Crabtree, K., & Swainston, K. (2023). Acceptability of a wellbeing coaching intervention based on socio-cognitive mindfulness: A qualitative study of coaches’ views. International Coaching Psychology Review, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsicpr.2023.18.1.21

- Crabtree, K., & Swainston, K. (2024). Integrating socio-cognitive mindfulness and coaching psychology: An intervention development study. The Coaching Psychologist, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.53841/bpstcp.2024.20.1.62

-

Crabtree, K., et al. (2024). A quantitative feasibility study of a wellbeing coaching programme based on socio-cognitive mindfulness. International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring, Special Issue 18, 134–149. https://doi.org/10.24384/sjz9-0t62

-

Crabtree, K., et al. (2025). How socio-cognitive mindfulness can enhance wellbeing coaching. The Coaching Psychologist, 21(1). https://doi.org/10.53841/bpstcp.2025.21.1.4

Your Next Step

If you’re curious about how these ideas translate into coaching practice, our free masterclass is a good place to start. It introduces the foundations of Positive Psychology Coaching and offers space to reflect on how this approach could support your development as a coach.